Our contributors all had interesting ways to render Joyce’s reckoning with guilt and his reality, as inspired by page 15.

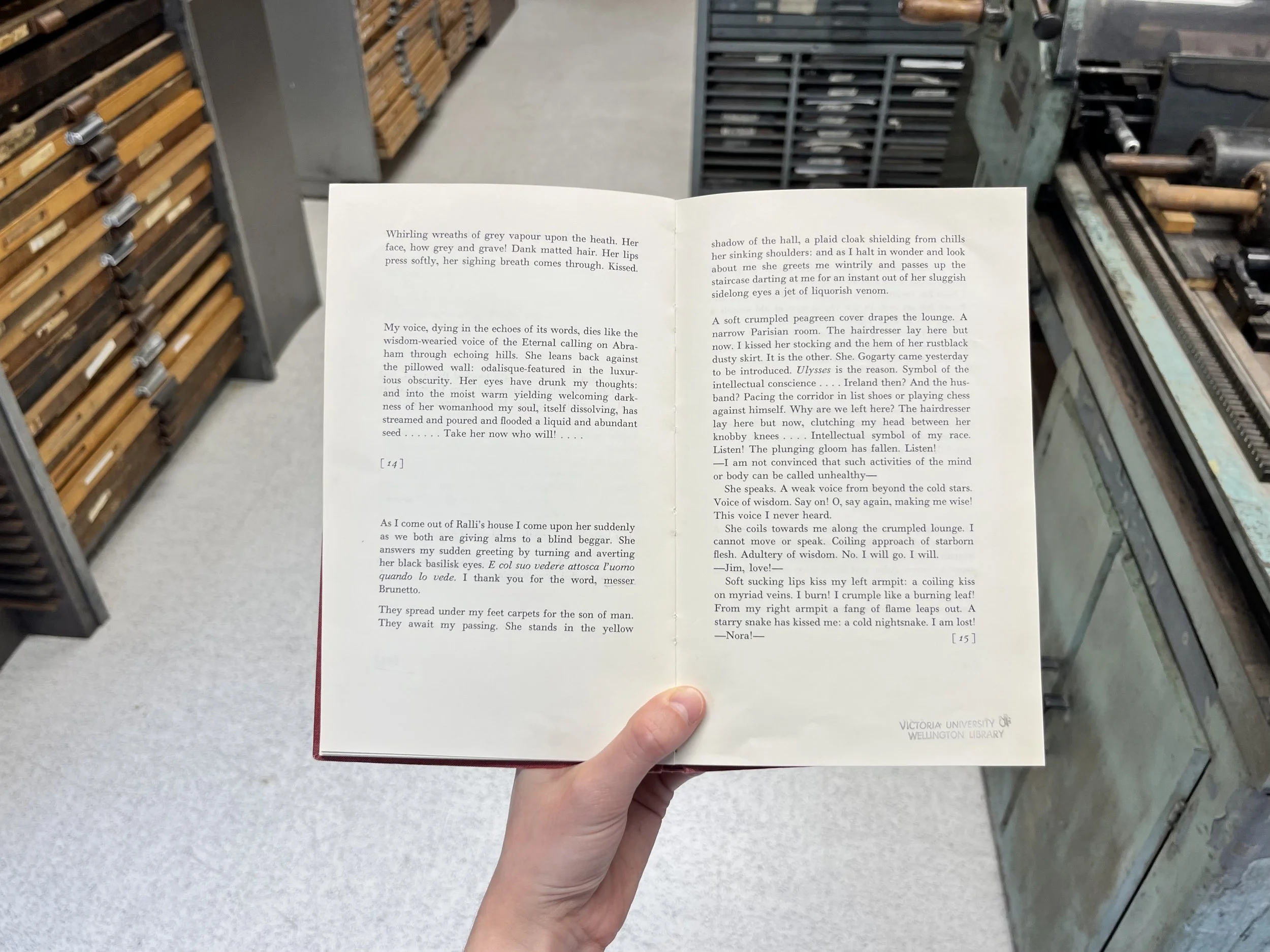

Joyce, Giacomo Joyce, page 15

SL

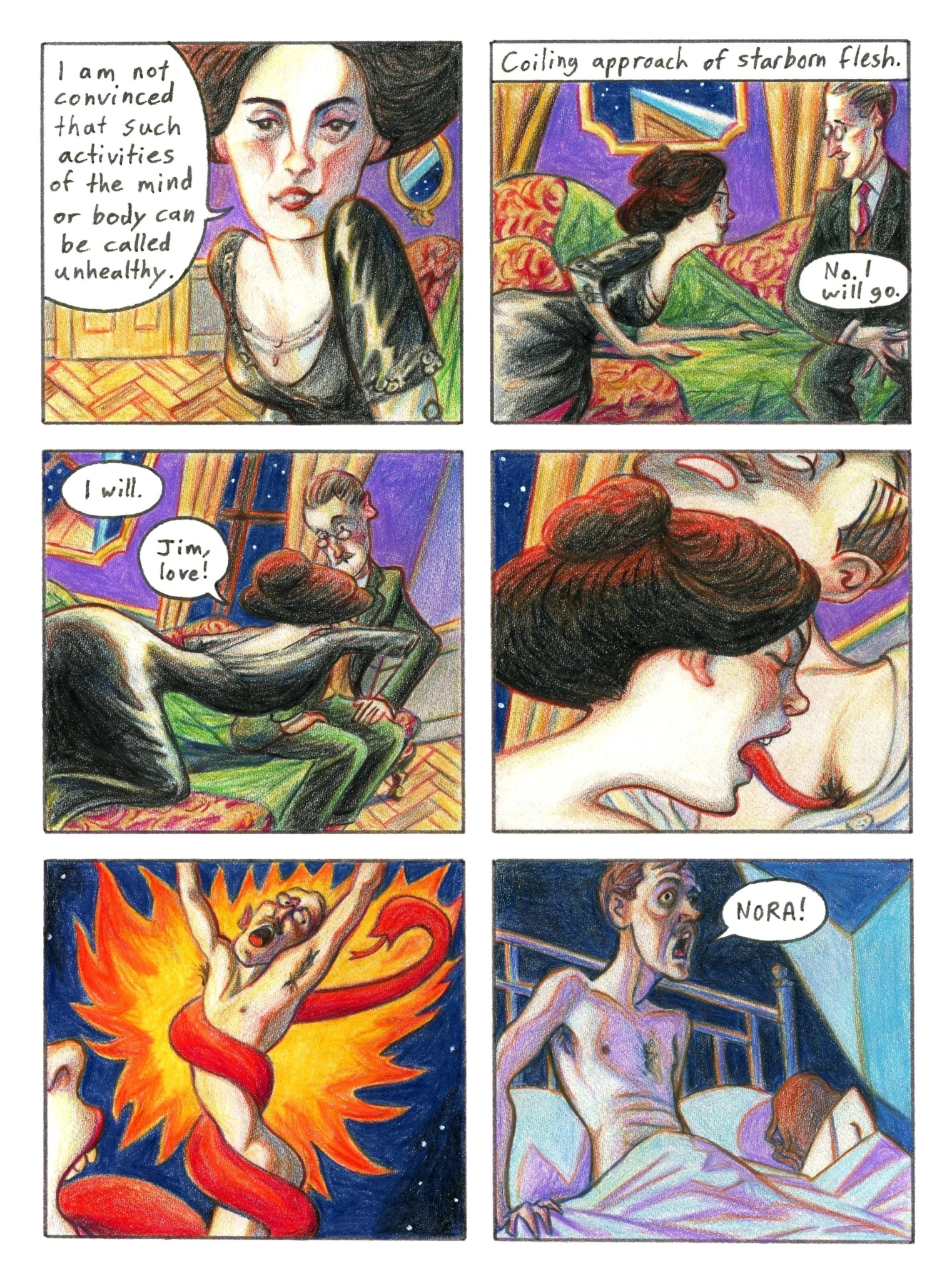

ED: I think you convey Joyce’s spiral into guilt, sin and vulnerability well with the image of Joyce naked and vulnerable against a backdrop of flames and the threatening onslaught of the cold nightsnake. This conveys Joyce’s coming to terms with his wrongdoings, and his conscience.

The snake coils around him, and we see the tree (presumably in the garden of Eden), which contextualises this snake as the image of temptation and sin. What does the two-headed snake represent to you? What of its two heads? What is the meaning of this climactic, violent vision?

SL

SL: I found this description visually rich and I thought I could do a better job of it. I must have had St Bernadette in the flames in my head when I drew this. And of course – I was brought up catholic – the snake had to be the serpent from the garden of Eden. I don’t know why I drew two heads. Perhaps I wanted to show that the snake was the same one as from the apple tree? Or perhaps there was a little bit of Medusa in it.

SL

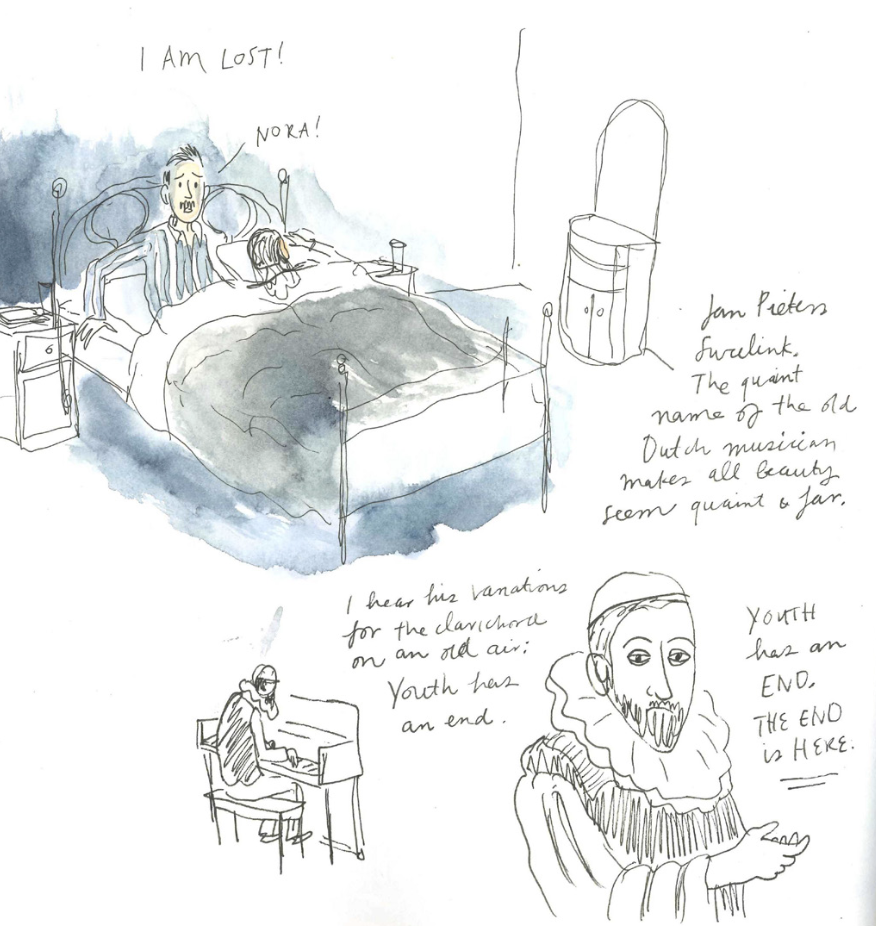

ED: We recoil from this fiery assaultive imagery to a gloomy, dark room where our narrator awakes, calling his wife’s name, who faces away from him in bed. You chose a high angle in the corner of the room – why? To observe from afar? Are we the narrator looking at himself? Or outside voyeurs looking in?

SL: I drew him from far away because I wanted to emphasise the coldness of his reality – the highness of his ceiling, the way that the night drains everything of colour. I also could see him sitting bolt upright after that nightmare/erotic dream and I thought that would be how it would play in a movie. So yes, I guess I was thinking of voyeurs – people watching the movie of this story.

JP

ED: There are few moments in your response, and even fewer pages, that are drawn with conventional comic ‘panels’ in your work. The only page that is illustrated entirely with uniform panels is the dream sequence.

I would like to ask you about the nature of panelling, because I know that the size, shape and frequency of panels on the page can deeply affect the pacing of the narrative, and the beats of the story. On this page, what did your series of decisions look like to arrive at the solution of six evenly spaced 1:1 panels? How does this relate to the unravelling of events experienced by the narrator?

JP: With this project I didn’t set out to create a comic per se; more of a “graphic response” that could accommodate a large variety of artistic and narrative approaches. Page 15 is the only one to really function as a traditional comic in that it features a continuous narrative sequence. It’s also very different from the other pages in that the original text is barely included, though it is referenced throughout. The images replace the words rather than interacting with them. I guess I chose this approach because the illustrated passage feels more narrative--less fragmentary—than the majority of Giacomo Joyce.

In terms of panel pacing, a sequence of evenly-spaced panels with the same dimensions creates a rhythmic quality that in this case, I hope, emphasizes the steadily escalating deliriousness of the scene.

TST

TST, Giacomo, 6:13-6:23

ED: Tyler, your wife is introduced at 6:18 and becomes a marker of reality amid a disorienting sea of red and green saturated desire.

The form of your film shifts with the introduction of the wife figure. This footage being comparatively candid and uncontrived supports a sense of documentary rather than fictitious film. Arriving at the third act there is an interesting push & pull between these two components (reality and fiction).

To me, this coincides persuasively with Joyce’s own reckoning with self in Giacomo Joyce. The wife figure seems to represent reality and memory; the other women, imagination/fantasy. What else does she represent to you? How does the way she is presented serve this desired impact?

TST, Giacomo, 7:33-7:40

ED: At 7:33, the cry ‘Erika!’ is audible over a clip of your wife, which then spirals into a spinning graveyard. Especially if this can be compared to the ‘Nora!’ moment in the original text, what does the wife figure represent to you? How does this shift and transform over the course of the film?

TST: By weaving my real life into the fictitious elements, this approach of documentary or persona filmmaking mirrors the way that Giacomo Joyce operates: Joyce’s own reckoning with himself. Cinema as a memory machine helps with this because it can conjure up real moments of the past, and this imaginative fantasy realm that is being created from the models that I film.

In this project, the wife represents reality, memory, reckoning with the self, commitment, guilt, responsibility; this person that you've set your life to.

It becomes very real; more real than even the black & white moments. She is presented in color and [is] overlapped or brought in to give a feeling of longing or desire or realization; of an anagnorisis, a turn, a surprise, a change in the mind that comes after this climax. Of recognizing that all you've been doing is looking and objectifying and gazing without guilt, with impunity, that's there’s this recognition that is addressed by the camera turning back on you.

TST: The wife figure I saw more as this Beatrice moment. This interaction was a call for help and an entrance into reality, but also a confrontation with a world that is very real and something that you have a responsibility to. This is hinted at throughout the film and then slowly starts to eat its way through with images of Erika, and then at the end Erika is being called for. I've put frames inside of a frames so that Erika appears over top of other women. So, at the moments in which desire is being enacted with other women, there's a call for a recognition of guilt; of the commitment that you have to your wife that you're not holding true.

TST, Giacomo, 7:50-8:01

ED: Where does this message land, at the film’s end?

TST: At the end there's a bit of pessimism in the fact that Giacomo has this sickening objectification of women and that returns. Even though Giacomo calls for his wife, and the relationship is broken off in some way with the young woman in the text, there's still a longing that is hinted at. The sickness returns in some way.

❦

It all begins with an idea —

Interpretation entails contrition: blaming yourself for loosening the grip of mea culpa maintains the remorse needed to consider the inconsiderable, to free freedom, to inspire inspiration.