A R E S P O N S E B Y W I T I I H I M A E R A

© Witi Ihimaera, 2023.

1.

Something surprising has happened.

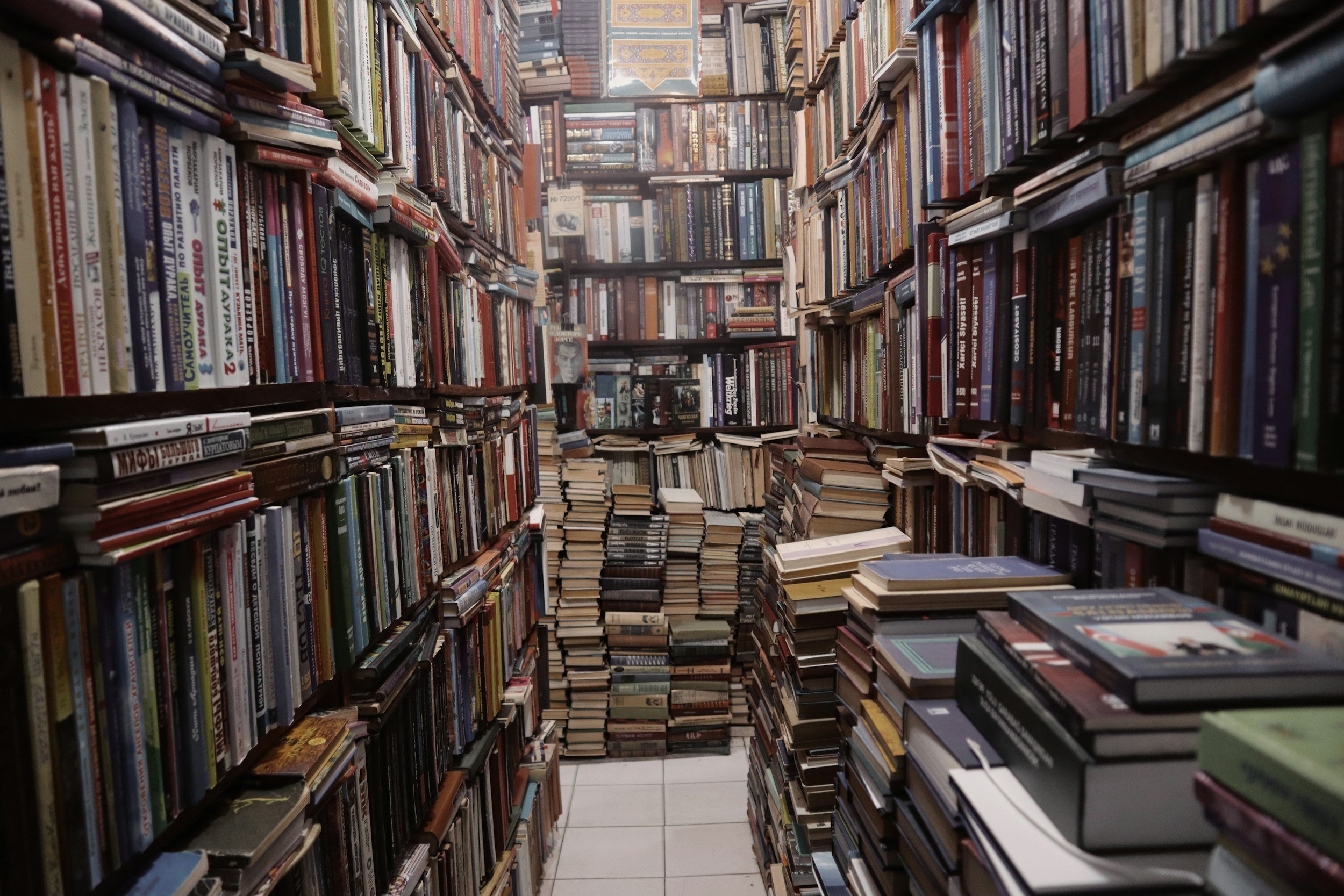

I am a rare books specialist, selling online from Berhampore, Wellington. The house looks ordinary from the street, almost decrepit with its peeling paint and rusting guttering. Appearances are deceptive however because when you come through the doorway, Open Sesame:

A cave that bibliophiles would lust to lurch into.

Six room are all hermeneutically sealed from sunlight, dust, the wet, the dry, whatever might soil and age all those pretty pages. Aerosol spray keep moths away from the delectable tomes old and young, first folios, signed author editions, stack upon stack of them, cherries ripe, full and fair ones come and buy. As for rats, my tomcat Billy prowls periodically for the pests.

In one room are a smattering and scattering of maps and manuscripts too.

A good wallow for all those wet-lipped collectors who prefer to follow me follow into my hollow, enticed by a Captain Cook journal paper or Katherine Mansfield letter or Te Rangi Hīroa lecture written in his own hand or Shakespeare first folio - ah yes, I had one of those, I almost didn’t want to sell it - but I splashed out on the Bentley, needs must.

I’ve been in the rare books business for some years and, being 75 now, have a reputation for keeping good quality stock sufficient to ensure the steady stream of punters arriving over the Internet or knock knock knocking at my door. To keep up supply I have a network of book hunters who fossick and forage, sift and scour, the secondhand and bargain shops that have sprung up during Covid; New Zealand is where rare books, aeroplanes with propellers, baby Austin’s and Caruso 78’s come to die.

And then, last month, that surprising event: a telephone call from a hospice in Whanganui. The venerable gateways to the dead are places where aged dames or gents who have kept some little golden precious, must part with it before they cark it, sigh, sniff, crocodile tears. Would I be interested in securing a long held valued object relating to an illustrious Irish writer? Some memento, missive or missal or handwritten manuscript in the author’s own writing and bearing his signature, perhaps, or dance card given to the object of his illicit amour?

With respect to the telephone call, I assume the proffered object to be a love letter: Oscar Wilde? I ask, affecting enthusiasm.

No.

Perhaps Jonathan Swift? I enquire with a touch of disappointment but sniffing out a steal.

I didn’t know he was Irish.

Perhaps, then, a minor writer in the Irish canon, I continue, like William Butler Yeats or Brendan Behan?

I am carrying on a pretence that this telephone call might not be worth the pother. You wouldn’t believe the bargains I have picked up and plucked from the ploy.

Oh…the caller replies, cuckolded by my apparent disinterest. How about something to do with James Joyce? Would that be of interest to you?

Jackpot.

2.

A week later I wait in my car outside Wellington’s airport terminal for the arrival of Emeritus Professor Gerald Ryan from the University of Otago, Dunedin. He is reputedly the foremost scholar of James Joyce in the country and I have secured his services to establish said letter’s provenance and to authenticate the object. I’ve paid a pretty penny for his services including a substantial fee, overnight hotel accommodation in a 4 star hotel in Wellington and all expenses paid.

I am expecting a venerable gentleman, an old(er) fart than I am to be awaiting me on the pavement, so imagine my surprise when, as the crowd thins, the only person left standing is a young dark scrawny lad who looks like he would hump anything that moves. He casts a look in my direction, rolls his eyes at the Mazda (I have learnt from experience that turning up to a prospective buy in the Bentley immediately trebles the price) and comes sauntering across.

Kia ora, you must be Mr Ffoulkes, he says, hoping I’m not. Professor Ryan couldn’t make the trip. He sent me along, Wharepapa Keelan, I’m his assistant.

Assistant my arse. This lad is Māori of the species Indigenous Ignoramus, how could he possibly be an academic’s assistant? And while he is a tasty morsel - in Dublin’s fair city where the lads are so pretty I first clapped my eyes on sweet Donny Malone - he’s not the kind of dark Joycean expert I expect to see wheeling his wheelbarrow through streets wide and narrow, singing cockles and mussels alive alive oh.

Catamite perhaps? I wonder.

I expect, at the very least, a doctor of Lit, I say in my best English enunciation.

I did my thesis on James Joyce, he responds, throwing his backpack into the rear passenger seat.

Trust me, if you had to wade through Ulysses 1922 and Finnegan’s Wake 1939 comparing the published texts against Joyce’s own manuscripts, you would know what his handwriting looks like, let alone his signature. Shall we go then?

I will certainly not be paying you the same commission as I had contracted with Professor Ryan.

Māori rates is it? he responds, scratching his ballsack so vigorously I cop a delectable sniff. I wouldn’t play that game if I was you otherwise I just might tell you that the item is a fake, double back after you’ve left, and buy it myself. So what’s it to be?

I thought I was a fox who could never be outfoxed.

Grimly I nod, gun the motor and we are off, Whanganui bound.

Over half an hour later, I am barrelling the Mazda past Porirua, and Forrymoppa or whatever he’s called, has been hunched down in his seat flicking his thumbs across his iPhone. I am not accustomed to being ignored by some young arsehole who is tantamount to…paid help.

So, Pottifocka, I ask in my kindest voice, organising a date on Tinder for tonight are we? Before we return to ditchwater dull Dunedin tomorrow?

He eyes me askance as if I have been looking over his shoulder and realises that he is being forced into making polite conversation. Closing his phone, he stares at me: Well?

Perhaps you could prove your credentials, I continue. What was the specific subject of your James Joyce research?

The haka in Ulysses, Wharepapa answers, picking his nose.

Aha, I answer, quoting from the haka:

Let us propel us for the frey of the fray! Us, us, beraddy!

Ko Niutirenis hauru leish! A la la! The Wullingthund sturm is breaking.

The sound of maormaoring! The Wellingthund sturm waxes fuercilier!

The Mazda weaves this way and that as I boisterously chant and Wharepapa pays more attention to me.

Whoa, yes, he nods. Joyce was living in Paris and, being a huge rugby fan, went to see France playing the All Blacks in 1925. He saw the great George Nepia leading the Ko Nui Tireni haka. Anyway, cut to six years ago and I was in my last year of Māori Studies and I read the haka. When Prof Ryan agreed to supervise my thesis I switched to Irish and Scottish Studies. Not as strange as you might think as on my Irish side my tipuna come from a castle in County Cork.

Which fortified house might that be? I venture. Caislen Caictarbh near Ballingcollig?

It’s a low blow but Wharepapa let’s it go by.

I looked at texts, contexts and cultural appropriation in my study of Joyce’s haka, he continues. I wanted to see if he was a dick and if his use of Māori taonga was cultural appropriation.

And?

He was and yes. But by that time I had been hooked into the complex and totally crazed creative way he manipulated structure and language. This might sound strange to you but Māori also have the same obsession and in many ways our approach in te reo, the relish and joy of it, is just as gargantuan, monstrous or Joycean…or…

Or?

Vice versa.

By the time I stop for petrol at Bulls I am more kindly disposed toward my unexpected companion. He’s more erudite than I thought he would be, so much so that I invite Wharepapa to join me for lunch at the Rangitīkei Hotel aka The Rathole when, really, I should have sent him off to find a hangi somewhere.

He orders the most expensive steak on the menu and a glass of beaujolais.

And what about you? Wharepapa asks me, chomping down his meat. When did you start reading James Joyce?

My interest is primarily bibliophileac, I begin. (Oh my, I am thinking, does my dark lad toss the boys the same way as he swallows?) Really, I don’t understand the cult that has developed around him or other Irish authors of the ilk of Behan, Samuel Beckett, Dylan Thomas…

Thomas was Welsh.

All those non-English writers then, I interject. In my opinion a whole academic industry has arisen supporting them only because they were modernists, trying to revolutionise writing.

You could put Katherine Mansfield in that list, Wharepapa answers, smacking his lips with satisfaction. Did you know that she met Joyce in Paris in March 1922? Her husband John Middleton Murry had published the first review of Ulysses ever; the three met in the company of mutual friend Sydney Schiff in the palatial cafeteria at the Victoria Palace Hotel. Mansfield was supposedly stupefied by the book and didn’t much like Joyce but he thought she had a better handle on it than her husband.

Stupefied would be a good way to describe my own reaction, I nod. I try to understand the moderns but, to be frank, I find trying to engage with their pretentious high expression rather like coitus non-startus. Always trying to outtalk, outwrite and outwit each other with their cleverness. And there was Joyce out in front and outdoing them. Am I spoiling your meal?

Do go on, Wharepapa continues with sarcasm, not meaning it.

In fact, I continue, waving my fork looking for someone to spike with it, I didn’t read Ulysses until the 1960s and only because I wanted to know why it had been banned in the UK and Britain from 1922 until 1933. Wasn’t that when an American judge lifted the embargo saying something like…while the effect on the reader of its sexual content is somewhat emetic nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac? I agreed with him entirely and the only way I could ever come to grips with the book was to see the movie in Wellington in 1967.

Wharepapa’s eyes grow wide as saucers. You were there? You’re a legend, mate.

I was 20 and a student at Victoria University. As you will know the film like the book was banned too in most countries but here at the bottom of the world the censor passed it.

Yes, Wharepapa nods, giving a burp at one end and a fart at the other. To much hilarity, and to the country’s eternal shame, the censor nevertheless decreed that men and women were not to see the film together.

I take a sip of my pale ale to stop coughing in mirth. The world thought we were mad, I recall, but at least we were better than good old Ireland itself where the fillum was not shown until 2000. However did you know that at the student session I went to, the theatre was organised slightly differently? A rope down the middle of the audience? We had to take our birth certificates as proof we were old enough to get in.

Ah yes…all those horny boys on one side and whimpering virgins on the other, never the twain could meet for a cop of a feel or open of fly and out comes Tommy to be brought to climax by a dainty hand during the dirty bits.

Trouble was that there weren’t any dirty bits, I tell Wharepapa. The film had been banned not for any visual transgressions, a flash of tit, hairy arse or penis but rather for its oral indiscretions: one mention of the word fuck and an extremely twee description of oral sex.

Your times were so tame, Wharepapa sympathises. Thank god for pornography.

I give him a sad look, let him think that way the dear boy. The frustration at the session I attended was so palpable that five minutes later I scored a toss from some anonymous lad in the toilets in Courtenay Place.

As we are getting back in the Mazda to resume our trip, Wharepapa is mellow enough to make an admission.

Professor Ryan sent me to Dublin on my first research trip, he begins and, until then, I never realised how great the divide was between the English and the Irish.

This was some years ago now but Heathrow when I landed after the long trip from the Antipodes was a huge hulking cephalopod of uncurling tentacle-terminals and linking corridors and I felt as I followed the signs to the gate to my Dublin flight that I was walking from one end of the world to the other the connections getting progressively dingier and dirtier and unkempt until I was delivered to this tiny gate with a shitty small waiting area for passengers getting onto the flight and I kid you not we would have to walk across the tarmac to get on the plane but here’s the fookin’ truth of it I looked at all my flying companions with their blood red hair and green asp-glittering eyes and pale elven faces the boniest I’ve ever seen and thought struth the Irish are ugly but I felt at home among them they looked like a coven of witches and warlocks straight out of a Beardsley drawing on their way to a coven-tion and I laughed like Hell and wondered why we just didn’t ride across the Irish Sea on our broomsticks.

And here’s the thing, Wharepapa says, staring me down. When I arrived in Dublin I realised how a writer like James Joyce could be born because in that city the English language had collapsed. The tight-arsed strait-jacketed construction of it had been subverted by a people in refusal of all that King James had to offer. The streets were filled with this terrible swound of sound and hollering and singsong of a language in crisis. The howl and wailing joy of it crashed in my ears, the collision and cracks as various histories - the Potato Famines that made the Irish the largest White diaspora in the world, let alone the Troubles and all of Ireland’s travails - let through ancient Gaelic evils upon the polite vowels and consonants of civilisation and unloosed the unspoken uncouth.

As we leave Bulls, Wharepapa adds a coda.

And it’s going to happen here in Aotearoa New Zealand, Mr Ffolkes, if it hasn’t already.

Although the young and brilliant Māori writer Coco Solid said to an imagined foreign audience who may or may not have understood strange New Zealand references - I can’t be James Joyce, sorry honey - maybe she and we haven’t recognised it yet.

3.

We arrive in Whanganui but because Wharepapa is not good at reading maps it takes us a while to find the hospice.

What kind of Māori are you? I ask him testily. Your ancestors were able to navigate all this way across the Pacific but you wouldn’t be able to get from one side of the road to the other even if the stars are out.

You have to upgrade to GPS, he mutters, like the rest of the world.

Finally we arrive at our destinynation, drive up to the door and park. Things are looking up. This particular establishment for the dying is decidedly upmarket with palatial buildings and red rose gardens, certainly not the haven for any cheap trinket-treasure.

I start rubbing my hands with glee.

I’ll do the talking, I tell Wharepapa. I don’t want you to queer my pitch. When I introduce you, what shall I call you?

As long as it’s not your boy, I’m sweet.

I put on my best professional smile as we enter and approach the receptionist. On our way I notice a wizened woman sitting in a wheelchair in the lobby, double parked there to enjoy the sun. As I walk past her she drops her knitting and, when she makes a plaintive move to reach it, her dressing gown opens and I get a whiff of the near dead. I hold my breath, look at the knitting, step over it, someone else will pick it up or the woman can do that herself.

She manages, however, to grab my left hand to look at it.

Oh, too gruesome to contemplate that touch! Horrid! I pull away, shuddering, and continue onward.

Good afternoon Madam, I greet the receptionist. I have an appointment with your Matron. My name is Ffolkes.

I note with a sideways glance that Wharepapa has picked up the aged crone’s wool and that she is mumbling to him.

Summonsed, the matron comes lumbering along the corridor like an overweight lioness. Mr Ffolkes? I wasn’t expecting you until tomorrow.

Tomorrow? I feign surprise, turning to Wharepapa. Did you get the day wrong?

Wharepapa gives me a look that could kill and utters a whispered expletive at me referring to the female orifice. I had forgotten to tell him that my policy as a prospective buyer is always to arrive a day earlier. Who knew what other possible purchasers the seller might have contacted? Better to be in the front of the pack.

Never mind, I say to the matron. Although my…assistant… and I have come all the way from Wellington we can book into a local hotel for the evening. It’s much too long a distance to go back to the capital and return tomorrow, don’t you think? Is there suitable accommodation at hand?

I am playing on sympathy of course, it always works.

Well…the matron begins. Seeing as you’re already here…oh, all right Mr Ffolkes, please come this way.

She shows me and Wharepapa to her office. The inscrutable sphinx in a wheelchair watches me as I cross her path again.

In the office the Matron turns a safe, twirls the knob, opens it and retrieves a small decorated box. Lifting up the lid, she exposes another object wrapped in a silk scarf.

This is the book that Mrs Bonica has asked us to sell on her behalf, the matron says.

Book?

Ever since receiving the telephone call last week I had been expecting to purchase a letter and had pondered on the possible history of how such a correspondence, signed by James Joyce, could end up here, in New Zealand. The most likely avenue would have been through Joyce’s younger sister, he nicknamed her Poppie, who had emigrated in 1908 to New Zealand as a Sister of Mercy with three other Irish novices. Poppie, who became Sister Mary Gertrude, was the one who had sent him the haka; likely she did a piano transcript for him as she was a musician. She lived most of her life in Greymouth, dying at 80 in 1964 after having undertaken a lifetime of penance and prayer for her profligate sibling. But I had understood that Sister Mary Gertrude had destroyed all the correspondence between herself and Joyce. However, perhaps one missive had somehow escaped being consigned to Hell and…

But…book? Ah well, I had come this far, perhaps I should look at it.

First, though, one must suffer through the matron’s narrative, to wit: Mrs Renata Bonica was a dementia patient, sob sigh so sad, at the hospice having been admitted some four years ago by her loving Italian family, second generation New Zealanders. She had come to our shining land with her parents as migrants after the Second World War from Northern Italy and, after some years living in the community of Italian fishermen in Island Bay, Wellington, had moved to Whanganui.

The book had belonged to Mrs Bonica grandmother. What did nonna have to do with James Joyce? I wonder. Perhaps he signed a first edition of one of his novels for her.

Ah well, maybe the book would at least have Joyce’s signature in it.

Don’t be too fast to dismiss this taonga, Wharepapa whispers in my ear. We sometimes forget that James Joyce lived in Italy for many years.

Of course, I reply, remembering that while Joyce is normally associated with Dublin, Zurich and Paris, he also resided in Rome and, especially Trieste, which was his favourite city. He went with his lover Nora and wrote his first novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, published in 1916, there. The earliest pages of Ulysses too. His two children Giorgio and Lucia were born in Italy.

The matron drones on and so does Wharepapa, he is earning his fee with his information.

Although Dublin was the main crucible for Joyce’s language, he continues, some experts say that it was honed in Northern Italy which historically had been part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

There, at the open thigh of Italy’s boot where Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia and Triestine-Venezia’s cultures conjoined he created his independent and extraordinary literary invention, the Joycean world. But…

But?

Something special happened between Portrait and Ulysses which made the latter the hyperspace object it became. Not just the language but also the overwhelming sensuality and sexual frankness of Ulysses. In 1968 Faber & Faber published some posthumous fragments from those years entitled Giacomo Joyce. In his introduction William Elliman points to its hero’s commotion over a girl pupil to whom he was teaching English. Joyce had many such pupils in Trieste, but he seems to associate his subject with one in particular, Amalia Popper who lived on the via San Michele.

The matron’s narrative has come to a stop. She has unwrapped the object.

Would you care to inspect the book Mrs Bonica is prepared to offer for sale, Mr Ffolkes?

I nod, put on my white handling gloves and lift the article from its coil of silk.

Questa Libra di Scuola

A.P.

Every page has stories written in one hand.

In the marginalia are copious comments on her creative abilities and illustrations made by her Irish teacher.

I am, to be frank almost pissing myself. Wharepapa sounds like he will break out with Ka mate ka mate.

However, at that very moment, the phone rings on the matron’s desk. Simultaneously there are raised voices from the vestibule. What is going on?

I smile pleasantly at the matron when she puts down the telephone. Does Mrs Bonica have a price in mind? I ask.

The matron has a strange look on her face. Before I can stop her, she has taken the book and scarf away from me, placed both articles back in their box and returned them to the safe. Standing in front of it she says:

I regret to say, Mr Ffolkes that Mrs Bonica has decided to retain her grandmother’s legacy.

My mouth opens and closes, opens and closes, butbutbutbuuuuuuu….

Thank you for coming, Mr Ffolkes. Good day to you.

I stalk out of the matron’s office.

The same old crone is sitting in her wheelchair in the lobby watching as we leave the hospice. I feel like kicking her, wheelchair and all, in the general direction of her Catholic god. She crooks a finger to Wharepapa spitting wet words in his ear but casting upon me her evil eye.

Vuole bollire le ossa di mia nonna perfare la minestra, she says to him.

Of course I hurry past, I don’t want her to shadow to cross my path.

What was that about? I ask Wharepapa when he joins me at the Mazda.

I don’t understand Italian, he answers.

4.

Oh but I do really, Ffolkes, I do understand Italian and what the kuia said to me.

And on the way back to Wellington from Whanganui, I can understand why you fulminate and fume about the collapse of the purchase of the taonga but it’s your own fucken fault really.

You should have picked up Mrs Bonica’s knitting.

Ffolkes gets so wound up about his coitus interruptus that I tell him to stop the Mazda. When he does that I jump into the back seat, put the earbuds into my two taringa to keep him out and take up my iPhone. I open it and see I have a number of hits on my Tinder account, choose one who looks like he gives as much as he will get.

And now I begin to doodle in Pages and from the ram of my brain spew random thoughts:

What happened to you Joyce in your inner creative world in Trieste to finally unlock your genius? was it the supposed unrequited desire for a schoolgirl who most probably was alarmed at the attention that her teacher was showing her? You were after all with Nora & was older than Amalia was maybe she ate garlic to give her stink breath to ward you away & look at you anyway you weren’t exactly the most attractive man when you think of those yunghung Italian studs who must have wanted to root her if only for the watchful eyes of her father God you were some groomer maybe? Waiting for her to tenderise on your cunning words eh Giacomo but it came to nothing downboydown - or did it - all that pentup Lust in you! All that romantic yearning stuff only exists in modernist novels or the poetry of old men If you had been living today you would have gratified yourself by dialling up some Thai-girli dating site & shuffled through the photographs and picked one but…is it that feeling of unrequited mess in EVERYTHING that did it, Giacomo, James Joyce my poor Irish sod? Opened the floodgates so all that energy came pulsing out like the slow bucking of penis when you come?

Nah, not just that…mush too simplistic to think only in sexual terms It’s gotta be more than that more than just one thing to have escaped the gelded nature of English and pushed it over the brink & why didn’t others follow you all those modernists talking on and on about craft & style & technique they didn’t jump over the cliff…you were too much too much

Oh Jamesyboy if only they had but instead it was back to the traditions they always railed against the hypocrisy of them all! And the river that could have been trickled along through the simpler means of poetry & poetics eh

As for you…all those languages and lust for mātauranga your head was filling and filling with it all until you found yourself babbling in a new and extraordinary way?

How long could you have sustained your language before it turned around and pushed YOU over the very edge you had pushed IT over?

Oh Mr Joyce forgive my ramblings who am I but some arrogant Māori prick living in the land where your sister is buried

Thanks be to Christ we arrive back in Wellington sooner than later on the whicketywhackety Wullingstund sturm waxing fuercilier coming up from the south hoya te heia, haere mai nga Tāwhirimātea ki te haka.

Not long after, the hotel looms up to greet me with the slamming of brakes. And Ffolkes is still in a mood, as if I giveashit. I have had his number for some time now.

I get out of the Mazda, pick my backpack up and hoist it over my shoulders.

Ffolkes has turned all wheedley and measly and meanmouthed. Could we try again? he asks. Let’s go back tomorrow. The old bitch would do it for you, he says. She would give you the book.

I feel like punching him in his soft stomach. Instead, Thanks for the ride and the hotel, I say.

You’ll be doubling back then, he spits.

And the wind unleashes itself:

Ko Niutirenis hauru leish! Ka tu te ihi hi!

The sound of maormaoring! Ka tu te wanawana!

Ki runga ki te rangi e tu iho nei tu iho nei!

Hii! Au! Au! Au!

It’s a centring, a return to the source.

Kaore, no, I say to Ffolkes as I remember the kuia’s words.

I slam the door shut, slamslamslamslam slam. And then I stare at him, kanohi ki te kanohi, so that he can see the whites of my eyes: I lifted up a rock, Ffolkes, and you were under it.

It’s too late to go back, I tell him. I would only be implicating myself in the trade of a preserved head.