Giacomo Joyce is written in fragmented scenes from Joyce’s mind and memory. These fragments are hugely expansive; they range from the micro to the macro scale as Joyce details everything from intimacy to isolation, in a landscape far from home.

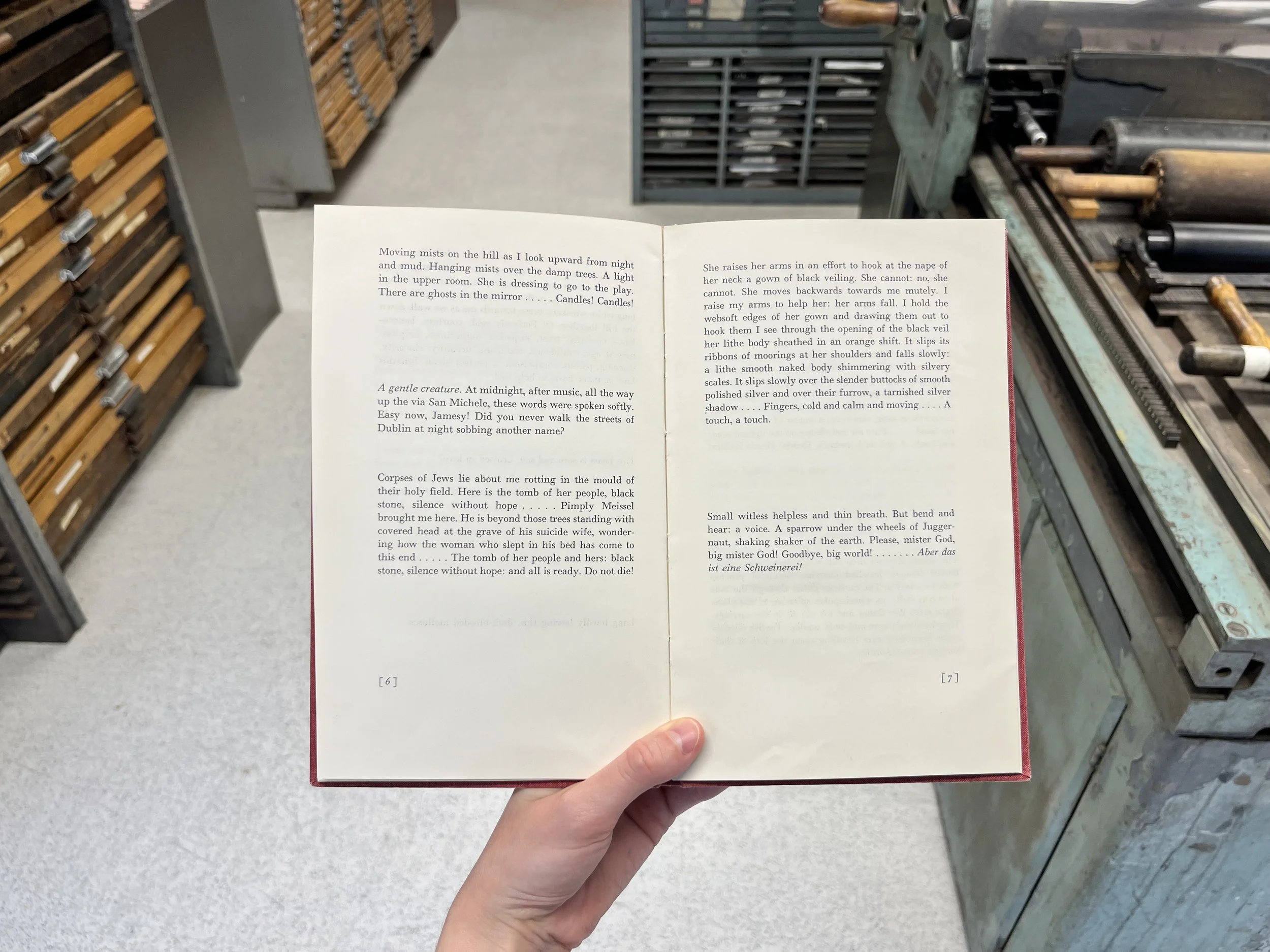

Joyce, Giacomo Joyce, page 6

JP

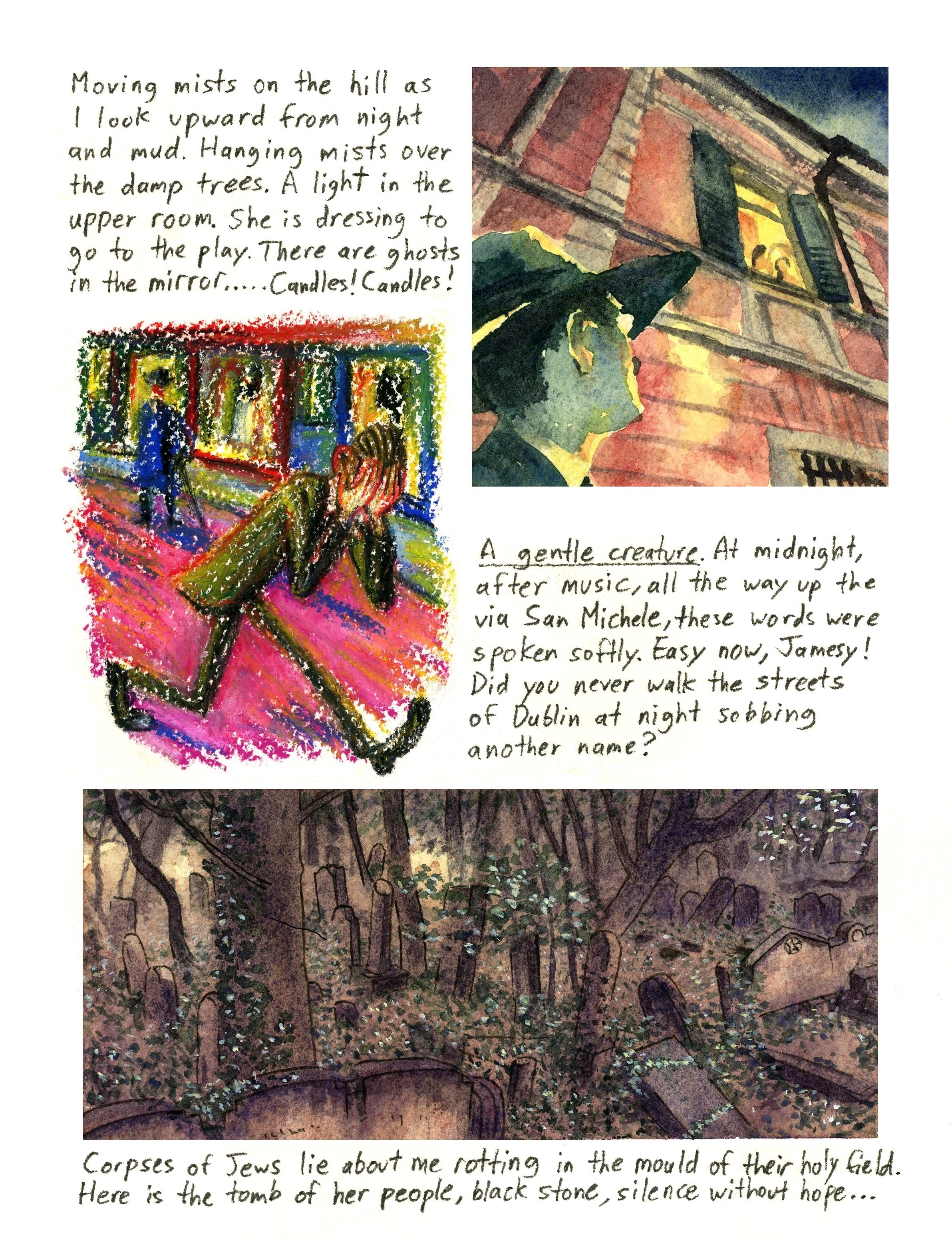

ED: I love your exploration of different mediums to express Joyce’s fragmented voice in Giacomo Joyce. How did the content of the writing influence which materials you chose to work with? A good example is page 6, which features three fragments of voice, and to coincide with them – three separately-distinct artistic renderings. What was the thinking behind what you hoped to achieve with these different visual tones?

JP: As I recall, the first panel, entirely in watercolour, was very loosely (and comparatively ineptly) inspired by the work of illustrator of Manuele Fior, particularly his illustrations to the classic French novel Le Grand Meaulnes (1914) by Alain-Fournier. Le Grand Meaulnes is largely the account of a romantic infatuation, and Fior’s approach seemed to me to also suit the evocation of Giacomo Joyce’s romantic idealization of his student as watches her at an upper window (and in mirrored reflection, further distorting the objectivity of his vision).

The second panel, in oil pastels, was somewhat vaguely inspired both in its colours and forms by the works of such Expressionist painters as Edward Munch, Otto Dix, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. These artists excel in the depiction of the subjective distorting effects of despair, often in an alienating urban setting.

The approach to the third panel was inspired by the work of a contemporary Japanese painter whom I really admire, Kazu Saitou. His works have a delicately muted yet almost otherworldly luminosity to them that I thought would be appropriate for the cemetery image. Unfortunately, I’m still extremely far off from figuring out how Saitou achieves his effects, but I’m glad to hear you say this first attempt to do so at least conveys a somewhat refined yet ghostly atmosphere.

SL

ED: I like how you fragment certain images of a scene. To illustrate page 6 of Giacomo Joyce, you’ve used spotted illustrations of the landscape, the house from far away, and then we zoom into the student’s window, and even closer, to the handles by her mirror. This is a great expression of how this ‘zooming’ function works in Giacomo Joyce, taken more literally and even more cinematically here. What do you hope this conveys to your audience?

SL: I loved this idea that you could zoom from a long way away in and in, until you were looking at the candles inside the mirror.

SL

ED: Nearing the final page of Giacomo Joyce, you portray the coming together of different narratives very interestingly – taking us away from the tunnel-vision of our narrator’s perspective, and placing him in the wider context of his reality. Beside Joyce’s window, his wife and child stand (Nora looking unhappy and dismissive). Below, a young woman plays on the piano. Joyce sits poised with his pen on the page, eyes wide, ready to write. What is the effect to you of showing these different side-narratives in your response?

SL: I always like it in movies – I’m thinking of Wes Anderson - when you can simultaneously see inside all the different windows of apartments. I like the idea that all sorts of different lives are going on. Joyce’s unhappy wife next door, someone else (not the student) playing downstairs. I like the idea that inside each space is another story, one that Joyce could possibly write. After all, that’s all he’s good for. Also, windows in apartments are like panels in a comic, so if you could see inside every apartment on a 5 story building, it would be like seeing an entire page.

TST

TST, Giacomo, 1:11-1:30

ED: At 1:15 there is a fast sequence of red and green images (demonstrating the push/pull between desire and clarity?) with choppy audio that races towards a comparatively quiet moment (1:25) that gazes across a large bay in black and white, with luminous light from the sky hazing the landscape. What does the natural world mean to you, in this context?

TST: In that scene in particular, there's a balance and push-pull in the movements between the red / green images. I wouldn't say between desire and clarity, I think both are kind of muddled in some sense, but the green and red images [evoke] long distance and short distance more than clarity and desire (while I think those kind of align in some ways). It's more about the vacillation between extremes and never having the balance between the two.

In terms of the quiet moment, the resolve, [we see a] bus seat, and so you're traveling outside of the city. The landscape is beautiful, but it's being contrasted against this sound that relates to the previous images of directly objectifying women. It’s an interesting moment to step outside of it, but to still be haunted by it. You can't escape the fact that these actions have already taken place, even as you move towards moments outside of the city or of light on the landscape, you're still held in tensions of the mind as it's working through these problems.

Black & white shots aren’t always natural, but there's usually a little more stillness to them; they do ground you. The purpose is to give you a sense of pacing; it gives you moments in which to rest, to work through the film and to see the way in which desire, even though it’s always pulling, and it holds on [even in] these moments—there is some sort of grounding ability in your life to hold yourself.

❦

It all begins with an idea —

Interpretation entails inscription: the hand that rocks the cradle and rules the world, inking itself new from the margins of what happened in the font-free alphabet of evolution.